Building Conway's Game of Life in 3D

I’ve been really fascinated with Conway’s game of life lately and I wanted to make my own implementation of his famous algorithm in 3D space. After looking around the internet, I found only a few examples of 3D versions of the algorithm, so I’d thought I would give it a go.

What is Conway’s game of life exactly?

Conway’s game of life is an algorithm that simulates changes in populations. For example, if there are too few rabbits in an area, the rabbit population will shrink in that area. If the population is too large, then the population will shrink due to overpopulation. The population size must be just right in order to grow and sustain life.

Conway’s game of life has two important properties. Firstly, cells in the game of life can reproduce themselves. Secondly, the game of life can simulate a Turing machine. This means that the game of life can be used to represent any calculation that a computer can do!

The game of life has 3 rules (via wikipedia):

- Any live cell with 2-3 live neighbors survives.

- Any dead cell with 3 live neighbors becomes a live cell.

- All other live cells die in the next generation. Similarly, all other dead cells stay dead.

2D Implementation

As seen above, this can be implemented easily using a HTML canvas. This can be done effectively in typescript using a 2-dimensional array to represent the grid:

export interface ICell {

value: number,

friends: number,

}

let grid: ICell[][] = [];

This is one of the results you can get. Notice the cells that keep flipping back and forth. These are called oscillators. In the top left, you can see cells being generated. The cells being generated that are moving down are called gliders, and are being created by the glider gun.

The code above can be optimized by storing the previous value and only changing cells that have changed. This reduces the number of calls that are made to the HTML canvas.

export interface ICell {

previousValue: number,

value: number,

friends: number,

}

After getting the HTML canvas working, it was pretty easy to move to phaserjs. I was able to use the same grid code. This is the glider gun.

Moving to 3D

Moving to 3D using babylon.js was pretty straight forward. All I had to do was add a 3rd dimension to my 2-dimensional array. Now, each dimension represents x,y, and z.

let grid: ICell[][][] = [];

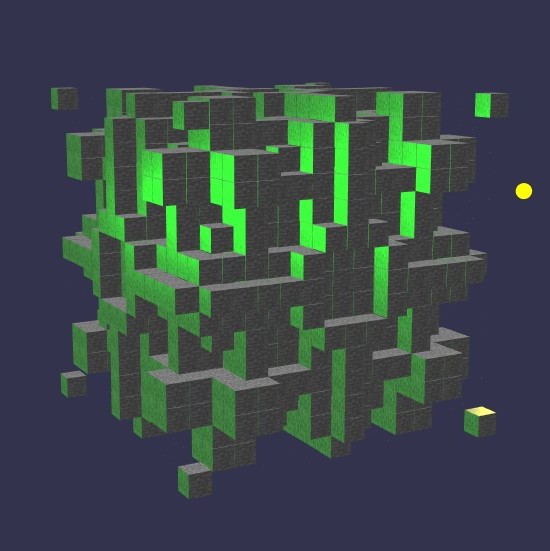

Below is how it looks:

And after adding some cool colors:

I also had to change the rules for the algorithm. In 2D space, a cell can have 8 neighbors, but in 3D it becomes 26 neighbors. After tinkering with the numbers, I came up with the following rules:

- Any live cell with 5-6 live neighbors survives.

- Any dead cell with 4 live neighbors becomes a live cell.

- All other live cells die in the next generation. Similarly, all other dead cells stay dead.

After making the change to the algorithm, this was the result.

Repeating Behaviors

I created the ability to randomize the starting population and found some really neat cell behaviors. I have taken the liberty to name them as well :)

The Stairs

This was the simplest that I could find. It repeats after 2 generations.

The Tube

The tube repeats every 3 generations.

The Cube

This is a cube that repeats every 3 generations.

The Glider (Not Found)

I have tried really hard to find a configuration that produces the glider behavior found in the 2D version. I am still in the process of discovering it. See if you can find the configuration by trying it out yourself. Let me know if you find any cool configurations!

Optimizing

In the above examples, for every possible location of a cell, there is a cube mesh. The cube mesh only becomes visible when the cell becomes alive. My grid for the 3D version is 19x19x19. This means that I have 6,859 cubes being rendered to the screen… that’s a lot!

This of course led to pretty poor performance (15 fps). To improve performance, if a cell was dead I would set the cube as not visible after it’s animation was finished. I also froze the positions of all the cells, as the cells don’t move after being created and so babylon.js doesn’t need to check for changes. The greatest performance benefit came from using only one material for all the meshes and making the meshes copies of a root mesh. This reduces the number of batches to the GPU from 6,859 to less than 100! As a result, the game now runs at a premium 60 fps!

Conclusion

Implementing the game of life in 3D was pretty straight forward, and it helped a lot to first test it in 2D, as the algorithm works exactly the same in 3D space as 2D space. The only change I did was change the rules to better fit the 3D space. This was also the first time using babylon.js, and it was pretty easy to use.

You can try the game out here. It includes all of the implementations discussed in this blog.